“While the storm clouds gather, far across the sea, Let us swear allegiance to a land that’s free”

– God Bless America, written by Irving Berlin in 1917, sung by Kate Smith and broadcasted to Americans on Armistice Day, 11 November 1938.

“…Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war”

– Prime Minister Menzies address to Australians at 9:15pm, 3 September 1939.

There is a feeling of anticipation that the current hot conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East and the simmering tension with China over the South China Sea could escalate into a massive war sometime soon. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, followed by the closure of McDonald’s Restaurants in Russia in response to Putin’s invasion, Thomas Friedman’s 1996 ‘Golden Arches Theory’ has well and truly been debunked. McDonald’s Restaurants do not deter war, globalisation, economic integration and technological innovation does not condition out the propensity for violence, conflict, war and tribalism.

In 2023 White men returned back to US Military advertisements and the US Senate will soon consider passing legislation that automatically registers American men aged 18 to 26 into the US Selective Service, the lottery draft.

War takes time to prepare. It is no coincidence that arrangements were made for Kate Smith to sing God Bless America on Armistice Day in 1938 in effort to generate patriotism among Americans who largely desired isolationism. President Roosevelt did not officially declare war on the Greater German Reich until 11 December 1941, three days after declaring war on Japan.

Mark Twain is said to have written that ‘History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes’. The anticipation of war was felt during the 1930s. Percy Stephensen wrote in his third instalment of his essay, Foundations of Culture, published in January 1936at section 45 on the topic, Bloodstained Europe, that despite Australia’s significant contribution and loss during ‘the war to end all wars’, Stephensen lamented:

‘The result, twenty years later, is that Europe is once again on the “brink” of another of its devastating depopulation adventures. Do the European statesmen, including the English statesmen, seriously believe that the young non – European nations will a second time join in European shambles if called upon to do so?’

The Berlin Olympics in August 1936 clearly did not allay for Stephensen the thoughts of a ‘devastating depopulation’ European war.

In the mid 1930s, Sydney born, William John Miles, then in his 60s was a man of wealth, through inheritance and from his work as an accountant and businessman. Miles was keen to use his wealth to disseminate his idea of Australian patriotism, primary being the concept of Australia first and Empire second.

In the classified section of the Sydney Morning Herald, Miles listed a position for ‘a secretary or research officer, who must be ‘Aryan’, to help him in a new political organisation’. Percy Stephensen fulfilled this role. Miles established a new journal, The Publicist, with the slogan, The Paper Loyal to Australia. Stephensen was largely responsible for the content of the journal.

Stephensen was born in November 1901, and described as ‘a child of the age, who became a warrior and a victim of words’. Stephensen was to live to see two horrific global wars, 1920s nihilism, devastating economic collapse and see firsthand the intellectual clash of fascism and communism.

The 1930s in Australia saw the growth of both fascistic and communist organisations. Australians put their faith in Prime Minister Lyons with his large Catholic family who occupied the Lodge as he tried to revive a stubbornly sluggish economy. The Spanish Civil War which became a hot war between fascism and communism drew much attention along with Stalin’s ruthless industrialisation in the largely primitive Soviet Union and Hitler’s determination to remilitarise the German Reich.

The Publicist printed speeches by Hitler and encouraged readers not to fight in the anticipated war in Europe. In the first issue of The Publicist in 1936, a satirical war recruitment advertisement was made stating:

WANTED 500,000 young Australians, must be physically fit, perfect in wind and limb for use in Europe as soil fertilizers. Apply, stating nitrate content of body, to No.10 Downing Street, England

This was followed by a satirical recruitment poster in the 1936 and 1937 editions of The Publicist discouraging Australians from fighting in Europe:

Don’t Go!

Your Country Needs You

Australia will be Here!

Stephensen’s coined catchy phrases which for the 1930s and 1940s were new for English speakers. Such terms included, ‘Jew-Yank’ and ‘Brit-USA-Com-Jew’.

Supporters of The Publicist began to meet together at cafes and from this came the Australia First Movement where discussions occurred on Australia’s reluctance to shed her colonial status, along with other topics of literature, art, religion and architecture. The policy position of the Australia First movement was articulated in The Publicist which included:

- Australian self – reliance and rejection of British imperialism, while still maintaining the Crown as Head of State.

- Promotion of Australian culture.

- Maintenance of a White Australia and support for natal policies to promote a higher birth rate.

- Less taxation and promotion of private ownership.

- Anti – communism.

In response to Menzies September 1939 declaration that Australia was at war with Britain, Stephensen wrote in The Publicist, that his aim was to create goodwill between Australia and Germany,

‘not because I held a brief for the Germans, but because I thought Australians were being mentally weakened by the revengeful Jewish campaigns of anti-Hitler hate which for years has flooded our Australian news press. If we are to fight against Germany, let us at least fight for an Australian, not a Jewish, reason.’

When the Australia First movement gathered at the Aydar Hall on Bligh Street, Sydney on 5 February 1942, violence broke out when subversive Communists in attendance began to accuse the attendees of being fascists and throwing eggs, chairs and letting off stink bombs. It was later recounted by an official from the Waterside Workers’ Federation that some wharfies went into the hall that night and stole a subscription receipt book, doxing the names of the attendees, which was provided to the Curtin government.

The Publicist was not an underground publication, it was for sale on newsstands and subjected to censorship by the intelligence organisations. Stephensen knew that spies were attending the Australia First Movement meetings and rallies.

Early 1942 has so far been the most threatening time for Australia, in late 1941 and early 1942 Commonwealth forces began to collapse in Malaysia and by 15 February 1942 the Japs were in occupation of Singapore. This was followed by the bombing of Darwin on 19 February 1942. Australia’s greatest enemy at this moment was Japan.

Despite there being no Australia First Movement in Western Australia, on 9 March 1942 four men from Western Australia who were subscribers of The Publicist, were detained pursuant to Section 13 of the National Security Act 1939 (Cth) where it was alleged the four were conspiring to assist Japan in the event of an invasion. Stephensen had no idea that a handful of his avid subscribers from Western Australia had been discussing plans to sabotage efforts of the Australian Defence Force to defend Western Australia from Japanese attack and in the event of invasion, make contact with the Japanese Army to establish an ‘Australia First Government’.

The allegations and detention against the four men from Western Australia who were subscribers of The Publicist resulted in Stephensen being detained at his house at 4:30am on 10 March 1942. Fifteen other people based in New South Wales were also arrested in connection with their involvement in the Australia First Movement and their written contributions in The Publicist.

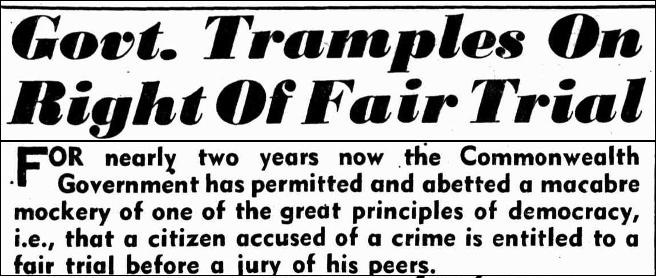

On 25 March 1942 Frank Forde, Minister for the Army exercised his ministerial power provided under section 26 of the National Security (General) Regulations 1939 (Cth) to keep Stephensen indefinitely detained in the absence of any criminal charge or trial. Forde’s speech before Parliament following Stephensen’s indefinite internment indicates the motive of the Commonwealth was to use Stephensen’s internment as a deterrent against dissenters who may associate with organisations contrary to Australia’s militaristic interests, with Forde stating:

‘I wish to warn people that, before associating themselves with any movement, they should assure themselves that it is bona fide and not an organisation which under the cloak of a pleasing name, is engaged in subversive activities.’

Stephensen was interred in the Loveday Internment Camp in South Australia and later at the Tatura Interment Camp in Victoria. Stephensen first avenue to challenge his internment was to apply to the Supreme Court of New South Wales for a writ of habeas corpus (which is where an inmate must proceed through the legal system to determine whether the detention is lawful). Chief Justice Frederick Jordan dismissed Stephensen’s application confirming Forde had the ministerial power under the regulations to detain Stephensen without trial.

The Commonwealth obtained legal advice from Harry ‘Fred’ Whitlam, father of Gough Whitlam who worked at the Crown Solicitors office that provides legal advice and representation to the Commonwealth. Mr Whitlam advised Attorney General, Herbert ‘Doc’ Evatt shortly after Stephensen’s internment that there was ‘nothing in any of that matter which appears to indicate any contravention by Stephensen of any regulations made under the National Security Act or of any other Commonwealth law.’ This explains why Stephensen was never charged for any criminal offence.

Stephensen obtained legal representation of Mr Walter Downing and preparations were made to commence action in the High Court claiming damages for wrongful imprisonment. Mr Downing engaged then former Prime Minister Robert Menzies, to give his advice as a barrister on the brief where Mr Menzies concluded that Minister Forde’s decision to detain Stephensen was valid pursuant to the Regulations, that his government introduced, and was unchallengeable.

Stephensen chose not to proceed with an application to the High Court. This case however, with current hindsight and the high court decision in Lim in 1992 would likely have been successful, as the crown had likely acted without lawful authority. In Australia’s constitutional framework, imprisonment, for a native-born Australian is a punishment that may only be metered out by, or in connection with, having a fair trial in a court of law and not by the arbitrary decision-making of the crown.

In March 1944 Australian Attorney General Evatt convened a Commonwealth Commission of Inquiry regarding the detention of Stephensen and the other internees. The Commission of Inquiry was presided by Justice Clyne at the Bankruptcy Court in Melbourne, which today would be the equivalent of the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) for General Federal Law. Stephensen was subjected to cross examination by Counsel for the Commission and Counsel for Military Intelligence and through this process no connection could be found between the Sydney based Australia First Movement and the four Western Australian men who discussed about conspiring with the Japanese. No evidence was found that the Sydney based Australia First Movement had contact with the Japanese.

Stephensen was released from internment at the invitation of Attorney – General Evatt on 17 August 1945, two days after Japan surrendered. In September 1945 Justice Clyne’s report was released where it was found that there were ‘substantial reasons’ for Stephensen’s internment.

The internment of Stephensen and the other 19 individuals was financially destructive for them as they sought legal action against their detention. Miles died just before Stephensen’s detention, his family refused to assist Stephensen’s unwell de facto wife and due to Stephensen’s detention, The Publicist was forced to close. The unfavourable outcome of the report by Justice Clyne towards Stephensen meant Stephensen was not eligible for compensation for his three-year internment.

Stephensen and the other individuals did not receive much support from the wider public who were collectively focused on Australia’s war efforts. Some branches of the Returned Service League demanded after the war that the government release the names of everyone interned during the war, though this request was declined.

Stephensen died on 28 May 1965 at the Sydney Savage Club just as he sat down after delivering a speech on the topic of DH Lawrence’s, Lady Chatterley’s Lover which was banned until the 1960s for obscenity. In the 1920s while Stephensen was a Rhodes Scholar, he was involved in the Communist branch of the Oxford University and one of his acts of defiance to Westminster was to smuggle copies printed in Europe of Lady Chatterley’s Lover into Britain.

Stephensen’s political shift from communism towards sympathetic views of fascism occurred in the mid 1930s. Stephensen returned to Australia in 1932 to a country experiencing social disruption from the depression, dreadful unemployment, bitter droughts and declining birth rates.

While Stephensen wrote Foundations of Culture, he did so amid being very poor. His de facto wife, Winifred Venus wrote in her diary on 14 January 1936, ‘…I produced my last shilling for cigs and we have only had a few oddments of food left which I had to part with to give —– a cup of tea…. I’d admired, the wireless starting to talk about strawberries and armfuls of food and in my book my eyes fell on a paragraph about food – ham which I enjoy – the word ham caught my eye and held it’.

Stephensen regarded his work of Foundations of Culture as a ‘Rubicon – crossing manifesto’, he also became disillusioned that democracy could solve the troubles of the day and Stalin’s Moscow Trials between 1936 to 1938 guided Stephensen away from communism. Stephensen further wrote about the ‘unholy trinity’ of British imperialists, communists and Jews and he maintained complete opposition to war with Germany. From this, Stephensen underwent a political transformation from being a communist in his 20s, to sympathy for fascism in his mid 30s.

‘History frequently makes attempts to repeat itself, but never quite succeeds in the attempt’

– Percy Stephensen, Foundations of Culture, Section 47: Australia is an Island.

I assume in September 1939 as Australia joined Britain in the war against the Greater German Reich, most Australians would not have known about the introduction of the National Security Act 1939 and the National Security (General) Regulations 1939. While the introduction of this legislation and corresponding regulation had no impact on almost all Australians who were being mobilised for war, it had a massive impact on the 20 Australians associated with Percy Stephensen. For Stephensen, it was financially destructive for him and his wife and it ruined The Publicist.

Percy Stephensen was interned for three years on the pretext of four Groypers (shall we say) in Western Australia discussing between themselves, in the absence of Stephensen’s knowledge, a fantasy that they could help the Japanese invade Western Australia to bring forth their idea of an Australia First government.

The Commonwealth interned Stephensen for the sole purpose to deter dissent in Australia at a time of crisis, but also amid substantial change. On 11 March 1942 General Douglas MacArthur arrived in Australia after escaping from the Philippines. General MacArthur took command of the Australian armed forces. On reflection, this was a massive turning point where Australia shifted from reliance since colonisation from Britain for maintaining our security and access to shipping lanes in the Asia – Pacific region towards dependency on Uncle Sam. Dependency that remains today and dependency that has got us involved in three bitter wars in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. All we have to show for our participation in these wars is migrants from the countries we helped the United States invade, living in our increasingly atomised country.

Stephensen was a risk to the Australian government as The Publicist would likely have been critical of the Australian government allowing American control of our armed forces.

My guess is that if Australia finds herself entangled in a hot conflict with the expectation to support the United States and fight overseas, the Australian government will do everything to prevent our atomised cities erupting into civil conflict, particularly if a group opposes Australia going to war against their ethnic country. The founding Anglo – Stock will be expected to fight for Australia as we have done before, but online dissidents may be very critical of this.

After all, why should Aussie men leave Australia while immigrants continue to stream into Australia in the name of maintaining cheap labour and preventing asset bubbles from bursting. Online dissidents may ask listeners or readers, is the war over there, or is it here? Indian’s have jumped at the opportunity to work in Israel post October 7 and Russia has enticed Indians to serve on the front lines to obtain Russian citizenship. The issue of replacement migration will not cease during war, it could entice its further expansion and the government may view outspoken dissent against this as prejudicial to Australia’s war efforts.

The internment of Percy Stephensen and the 19 other individuals associated with the Australia First Movement during World War Two must be a reminder to us all that our government has the capacity to quickly introduce laws and regulations that can swiftly intern individuals deemed to be prejudicial to public safety or the defence of the Commonwealth. The definition of what is meant by ‘prejudicial’ or other such term in any future legislation, will inevitably be a partisan decision made by the government of the day.

“Why am I in this narrow yard?

You ask. Well, I will tell you why.

Outside some say that I should die.

So here they brought me, stood the guard.

There, shut the gate, made the barbed wire high,

And all because so far as I can see,

I loved my country and they hated me”

Harley Matthews, 1 April 1942 – returned WW1 serviceman who engaged in the Gallipoli campaign and was interned for being a member of the Australia First Movement.

Contributed by James Smith.

Bibliography:

- Muirden, Bruce, The Puzzled Patriots: the story of the Australia First Movement, Melbourne University Press, 1968.

- Munro, Craig, Inky Stephensen, Melbourne University Press, 1984.