It’s Banjo Paterson Day today, and I thought I had better write a reflection on why this day is so important to Australian Nationalists. Nationalism, not as a descriptive term but as a positive ideology, was hugely influenced by the Romanticism of the 19th century. We can think of figures like Johan Gottfried von Herder and his conception of the nation as a product of geography and language, holding to a fairly strong form of linguistic relativity. Alongside Herder, we could also look to Fichte and his patriotic Address to the German Nation against the Napoleonic occupation. But the real strength of Romanticism in expressing and developing national identity is not in words, but in music, art, and poetry. On this day of perhaps our greatest national poet, Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson, it is well worth discussing the role of art in shaping the national consciousness of the people.

Many a modern academic has argued that nationalism was simply invented out of whole cloth in the 19th century by bourgeois ideologues, but this is a fundamental misunderstanding of what occurred. European Romantic composers such as Tchaikovksy and Bartók did not simply invent music for their nation out of thin air, but went out to the people and recorded and collected their folk music as inspiration for their own work. Through this ethnomusicological effort, the Romantic Composers managed to capture the spirit of the folk particular to their nation and express it in the form of Western high culture. To understand what I’m talking about, stop here for a moment, and go put on Colin Brumby’s Swagman’s Promenade and give it a listen. When you’re done with that, you might like his Festival Overture on Australian Themes too. Music is not something innocuous, it has the power to shape the soul. We must have the souls of true Australian men. The man who can listen to a piece of music like the Swagman’s Promenade and not feel a stir in his heart of love for his people, culture, and heritage is a man who has been so totally alienated from the most fundamental experiences of human existence that he has been reduced to a brute and slave.

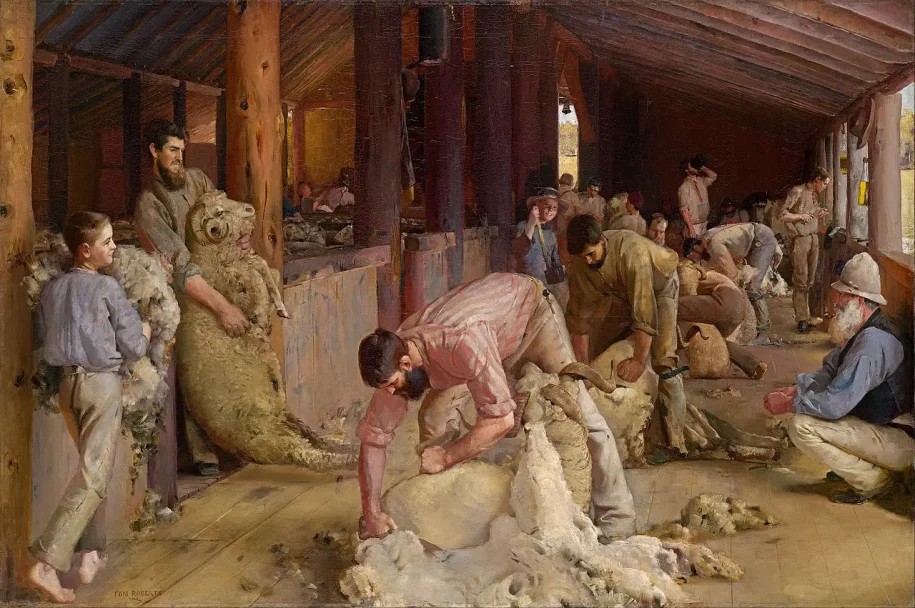

The spirit of the Australian folk was most clearly captured in the late 19th century poetry of Banjo Paterson, in such poems as The Man from Snowy River, Clancy of the Overflow, and Song of the Federation. Our most famous and well-known song, Waltzing Matilda, carries the words of this great man. It is said that Banjo lived at a time when Australian bush culture was already fading into the past. Nonetheless, through his great literary output Paterson ensured that the spirit of the bush would never be forgotten. As he writes in Clancy of the Overflow:

In my wild erratic fancy visions come to me of Clancy

Gone a-droving ‘down the Cooper’ where the Western drovers go;

As the stock are slowly stringing, Clancy rides behind them singing,

For the drover’s life has pleasures that the townsfolk never know.

And the bush hath friends to meet him, and their kindly voices greet him

In the murmur of the breezes and the river on its bars,

And he sees the vision splendid of the sunlit plains extended,

And at night the wond’rous glory of the everlasting stars.

This contrasted with the “dusty dirty city” full of the “stunted forms” of the townsmen. This is Stephensen’s “race and place”expressed strongly in literary form, and there are still men who will hear the call of the bush reaching out to their innermost being through these verses. It is this cultural power that rises up from the very earth that we must draw upon. Paterson’s writing of the lyrics of Waltzing Matilda for Christina MacPherson, and her setting it to music, is a clear example of the original power of folk culture. It is the power that gives life to the high culture of Brumby’s Swagman’s Promenade, keeps it rooted in the Australian soil, and prevents it from becoming just another nice cosmopolitan tune. It is this power that has found expression in countless patriotic expressions of this basic musical idea, in Jack O’Hagan’s God Bless Australia (a better national anthem, in my opinion) and in the Australian Army March. This is not a power that is crudely “invented;” it is the manifestation of a whole racial feeling.

At the beginning of this post, I mentioned Fichte’s famous Address to the German Nation. At the time Fichte was writing, the German nation was split into many small states, many of which had fallen to Napoleon due to their disunity. In Australia, we are not yet faced with a total foreign occupation; however, we live under a regime that is totally hostile to Australian nationalists and patriots. Most of our economy is foreign owned. We may not be split into different political entities – yet – but true Australian nationalists are spread far and wide geographically and there are many isolated individuals who hold to nationalist beliefs but are too frightened by the possibility of state and para-state persecution to involve themselves in the movement. It is far past time that we begin to unify our nation, to celebrate our culture, to organise politically under the auspices of the Australian Natives’ Association. We must acknowledge that we no longer live under a truly Australian state. That state has been colonised by traitors, parasites, and foreign interests who look with suspicion upon the man of principle who holds to real political ideals. They hate that which our national art loves and expresses. When we recognise that the state does not represent us, we must organise under the banner of an organisation that truly preserves our heritage as a people and plans for a bountiful and secure future for our posterity.

What can we learn from the Romantics? Some have argued that it is inorganic to embrace the Australian culture of the past since modern multicultural society has so disconnected the average Australian from that culture. On the contrary, like the Romantics we can and must be intentional in connecting with our folk culture as much as we can, for in doing so we will be inspired by the spirit of our folk, the subtle power of our people, when we create the Australian high culture of the future.

Elias Priestly,

ANA, Victoria